This content is sponsored by Passy Muir

Co-Author: Michael S. Harrell, BS, RRT (Director of Education – Respiratory, Passy-Muir, Inc.)

Impact of Tracheostomy Tube Cuffs on Swallowing

Tracheostomy tube cuff status often arises as a consideration as it relates to swallowing. What impact the cuff may have on swallowing is a frequent question and one that is important in the management of patients with both dysphagia and a tracheostomy. A reason for closely monitoring tracheostomy tube cuff status is that it may have a negative impact on swallowing. While a consensus does not exist in the research, it has been reported that an inflated cuff may impinge upon swallowing by tethering the larynx and reducing hyolaryngeal excursion during the swallow. Another reported impact is that an over-inflated cuff may impinge on the esophagus, causing reflux of ingested substances. However, research has shown that use of a Passy Muir Valve improves swallowing and reduces aspiration more often and more significantly than cuff deflation alone (Suiter et al., 2003).

Amathieu, Sauvat, Reynaud, Slavov, Luis, Dinca, … Dhonneur (2012) conducted a study looking at incremental increases in cuff pressure for patients with tracheostomy and measured the impact on the swallow reflex. They found that as the cuff pressure increased, the swallow reflex became increasingly more difficult in both latency and magnitude. Their findings indicated that any pressure above 25 cmH2O has a significant risk for negatively affecting swallowing. This consideration becomes even more significant when considering the role that swallowing function plays in weaning a patient from both mechanical ventilation and from a tracheostomy tube.

A study by Ding and Logemann (2005) investigated swallowing in both a cuff inflated and cuff deflated conditions. They found that the frequency of reduced laryngeal elevation and silent aspiration were significantly higher in the cuff-inflated condition as compared to the cuff– deflated condition. Changes in swallow physiology also were found to be significantly different among various medical diagnostic categories. The researchers suggested that these findings indicate a need to test both conditions during a swallow study. It would be important to know the potential impact of a cuff with individual patients, leading to having both a cuff up and a cuff down condition during both FEES (Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing) and MBS (Modified Barium Swallow study).

In a recent systematic review, Goff and Patterson (2018) analyzed multiple studies and concluded that patients with a tracheostomy should be evaluated for possible swallowing impairment, regardless of cuff condition. They also suggested that patients should be seen and evaluated on a case-by-case basis to determine the safety of swallowing for return to oral nutrition. These recommendations were suggested because the research to date has not reached a consensus in order to establish a standard of care for tracheostomy and cuff management as they relate to swallowing.

Impact of Team Management

The complexities of managing this patient population lend themselves to being managed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT). It has been demonstrated that a team of appropriately trained professionals, armed with evidence-based guidelines, significantly improves care and reduces negative outcomes for the patient with tracheostomy (de Mestral, 2011; Speed & Harding, 2013). A team approach assists with continuous monitoring, proper cuff management, and the patient care plan.

Working with patients following tracheostomy and with mechanical ventilation takes a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to ascertain that the needs of the patient are well met. Because of the complex nature of working with these patients, having the involvement of different disciplines provides perspective on the multifaceted needs of a patient with tracheostomy. Typically, these patients are followed by both a respiratory therapist (RT) and a speech-language pathologist (SLP). However, many other healthcare professionals are trained and involved with the tracheostomy and use of the Passy Muir® Valve for communication and swallowing. To initiate a MDT approach, it takes multiple healthcare professionals, including the physician, nurses, dieticians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists and the patient, at the center of it all.

In a study conducted by Fröhlich, Boksberger, Barfuss-Schneider, Liem, & Petry (2017), they investigated best practice for early intervention with use of the Passy Muir Valve as a standard of care in the ICU following tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation. Their findings demonstrated that patients improved with voicing and swallowing more quickly than those without MDT intervention. However, since the authors were able to follow the patients over an extended period of time, which included up to 51 trials with the PMV®, they also reported how the implementation of a team approach had a positive impact on potential adverse events, with none occurring. The researchers attributed these outcomes to the multidisciplinary team approach and suggested the findings support the idea that two professionals should be at the bedside to provide assessment and intervention with the PMV, especially when used in-line with mechanical ventilation.

Santos, Harper, Gandy, & Buchanan (2018) also investigated the impact of team management on the post-tracheostomy care of patients. Their findings concur with Frohlich, et al (2017) and suggest that having the involvement of an MDT allows the patient to progress faster in multiple areas. The parameters addressed in their study were time in the ICU, total hospital days, days to Valve use, days to verbal communication, oral intake, and decannulation. The group receiving team management were found to have improved care in all areas measured. Patients who received the Valve with the MDT did so earlier in their care and had restored voicing, communication, improved swallowing, and the ability to participate in their care. The positive impact of an MDT on the care of patients and the ability to achieve earlier voicing cannot be understated in its clinical significance. As with any medical procedure or device, thorough education is important in achieving the desired outcomes. Providing the education and competency verification necessary is the duty of the organization providing healthcare services.

It also is the responsibility of healthcare professionals to provide the best possible care for their patients. Proper cuff management, including cuff deflation, contributes significantly to the best practice plan of care for the patient with a tracheostomy. Proper cuff management also leads to earlier intervention for communication and swallowing. The safety and efficacy of the plan depends largely on the education and competency of the team caring for these individuals, as well as a commitment from the healthcare facility to a multidisciplinary tracheostomy team approach for patient care.

Purpose of a Cuff

First, the purpose of the inflated tracheostomy tube cuff is to direct airflow through the tracheostomy tube and into the airway during inflation. This occurs typically during mechanical ventilation because a closed ventilator circuit allows control and monitoring of ventilation for the patient. Frequently, the patient has a more seriously compromised system than patients who are not on a ventilator. The inflated cuff also may be important in cases of gross emesis or reflux when aspiration of gastric contents may occur; the cuff may assist in limiting the amount of aspirated material entering into the lower airway.

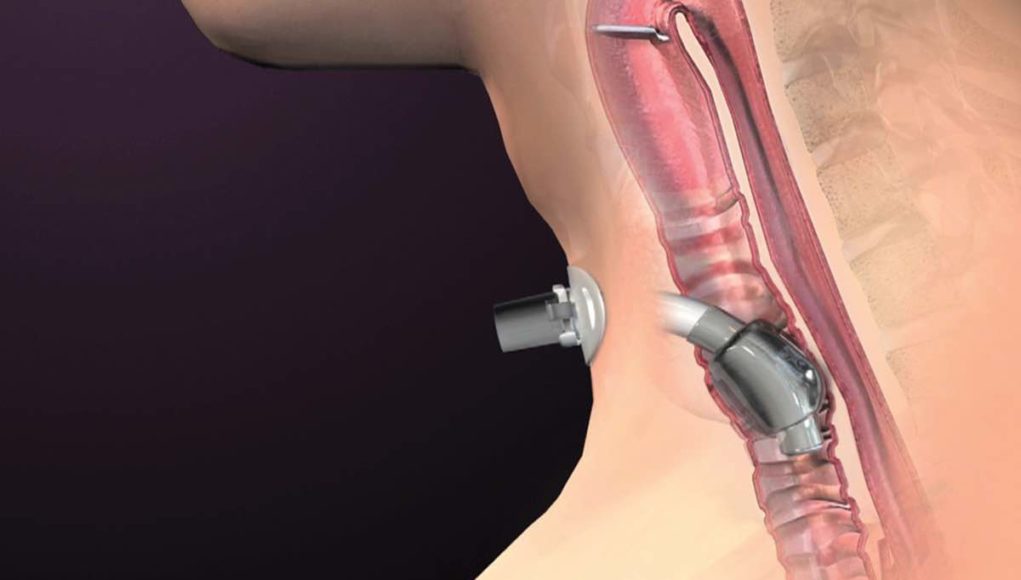

While the cuff may assist during episodes of gross aspiration from gastric contents, the primary purpose of the cuff is for mechanical ventilation. The perception that a cuff helps to eliminate or significantly reduce the occurrence of aspiration is false. The definition of aspiration is when any food, liquid, or other matter passes below the vocal folds. Therefore, the cuff cannot prevent aspiration as it also is located below the vocal folds (see Figure 1). When neither mechanical ventilation nor a risk of gross aspiration is present, the cuff should be deflated. Another consideration is to change the patient to a cuffless tracheostomy tube.

Management for Cuff Inflation

The inflated cuff should be avoided whenever possible because it has the potential to cause multiple complications, such as:

1) Increased risk of tracheal injury, including mucosal injury, stenosis, granulomas, and more;

2) Diminished ability to use the upper airway, leading to disuse atrophy over time; and

3) Restriction of laryngeal movement (laryngeal tethering) which may impact swallowing negatively.

If a patient requires an inflated cuff, then the manner in which it is being inflated should be considered. The complications that have been reported with tracheostomy tube cuffs may be avoided by ensuring proper management. Three methods which are commonly used to inflate a tracheostomy tube cuff are use of a cuff manometer (or cufflator), minimal occlusion volume, or minimal leak technique. While some guidelines provide that cuff pressure should be between 20 – 25 cmH2O, others suggest 15 – 30 cmH2O (Credland, 2014). The disparity that exists between resources makes it imperative that healthcare professionals understand the potential impact and how to manage a cuff properly. Using the pilot balloon or pushing air into the cuff by syringe without a stethoscope places the patient at high risk of an improperly managed cuff which may cause inappropriate inflation leading to damage or impairment. Dikeman and Kazandjian (2002) recommended that cuff inflation always occur with the use of manometer or stethoscope.

Management for Cuff Deflation

Deflating the tracheostomy tube cuff, when appropriate, has been shown to have multiple patient benefits, including:

1) Reducing the risk of potential tracheal mucosal damage;

2) Returning the patient to a more normal physiology, including closing the system by using a bias-closed position, no-leak Valve;

3) Restoring speech and improving communication;

4) Allowing for the possible improvement of the swallow;

5) Potentially lowering the risk of aspiration;

6) Allowing rehabilitation to begin as early as possible; and

7) Decreasing the time to decannulation.

Cuff deflation is recognized as an important step in the care plan for a patient with a tracheostomy (Speed & Harding, 2013). The benefits of cuff deflation can be safely and effectively extended to a patient with mechanical ventilation and use of the PMV, when appropriate assessment and patient selection is performed (Sutt, Caruana, Dunster, Cornwell, Anstey, & Fraser, 2016). This early cuff deflation may decrease delays in the rehabilitation process and potentially avoids the negative consequences related to the inflated cuff. The earlier that a patient has their cuff deflated, the earlier the patient may be weaned or decannulated. When decannulation is not a possible goal, cuff deflation may still accommodate benefits related to communication, swallowing, and other functions.

Care of patients with a tracheostomy has become a frequent topic of discussion in the medical industry and publications. Due to this focus on the care and interventions for patients with tracheostomy, details related to the care plan of these patients are of concern and must be based on evidence-based practice. One significant aspect of patient care following tracheostomy is the safe and efficacious management of the cuff, especially when using a bias-closed position, no-leak Valve. Proper cuff management is essential when assessing and treating patients for communication and swallowing.

References

Amathieu, R., Sauvat, S., Reynaud, P., Slavov, V., Luis, D., Dinca, A., … Dhonneur, G. (2012). Influence of the cuff pressure on the swallowing reflex in tracheostomized intensive care unit patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 109(4), 578-583. doi:10.1093/bja/aes210

Credland, N. (2014). How to measure tracheostomy tube cuff pressure. Nursing Standard, 30(5), 36-38. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.5.36.e9495de

Mestral, C. (2011). Impact of a specialized multidisciplinary tracheostomy team on tracheostomy care in critically ill patients. Canadian Journal of Surgery, 54(3), 167-172. doi:10.1503/cjs.043209

Dikeman, K. & Kazandjian, M. (2002). Communication and Swallowing Management of Tracheostomized and Ventilator-Dependent Patients. 2nd ed. Thompson-Delmar: United States.

Ding, R., & Logemann, J. A. (2005). Swallow physiology in patients with trach cuff inflated or deflated: A retrospective study. Head & Neck, 27(9), 809-813. doi:10.1002/hed.20248

Fröhlich, M. R., Boksberger, H., Barfuss-Schneider, C., Liem, E., & Petry, H. (2017). Safe swallowing and communicating for ventilated intensive care patients with tracheostoma: Implementation of the Passy Muir speaking valve. Pflege, 30(6), 87-394. doi:10.1024/1012-5302/a000589

Goff, D. & Patterson, J. (2018). Eating and drinking with an inflated tracheostomy cuff: a systematic review of the aspiration risk. International Journal of Communication and Language Disorders, 00(0), 1-11. DOI: 10.1111/1460-6984.12430

Santos, A., Harper, D., Gandy, S. & Buchanan, B. (2018). The positive impact of multidisciplinary tracheostomy team in the care of post-tracheostomy patients. Critical Care Medicine, 46(1): 1214.

Speed, L., & Harding, K.E. (2013). Tracheostomy teams reduce total tracheostomy time and increase speaking valve use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Critical Care, 28(2), 216.e1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.005

Suiter, D. et. al. (2003). Effects of cuff deflation and one way speaking valve placement on swallow physiology. Dysphagia, 18: 284-292.

Sutt, A., Caruana, L.R., Dunster, K.R., Cornwell, P.L., Anstey, C.M., & Fraser, J.F. (2016). Speaking valves in tracheostomised ICU patients weaning off mechanical Do they facilitate lung recruitment? Critical Care, 20(1), 91. doi:10.1186/054-016-1249-x