Co-Author: Dr. Jacqui Allen

Pharyngeal Constriction

Poor pharyngeal constriction is one of the most common swallowing deficits reported in swallowing clinics 1. Pharyngeal weakness is seen across many common conditions: Parkinson’s disease 2, brainstem stroke 3, anterior cervical spine surgery 4, head and neck cancer5, myotonic muscular dystrophy6 and Zenker’s diverticulum 7. Figure 1 demonstrates impaired pharyngeal constriction across aetiologies.

What is pharyngeal constriction?

Pharyngeal constriction refers to the three-dimensional contraction that occurs through the pharynx, upper esophageal sphincter and then traverses into the peristaltic oesophageal wave. Primarily produced by sequential constrictor contraction, it impels bolus through the pharynx and pharyngoesophageal inlet in combination with negative pressures generated within the oesophagus and hyolaryngeal distraction. If pharyngeal constriction is reduced, it implies overall pharyngeal weakness and reduces the ability to pass the bolus distally.

How can we measure it?

Residue in the pharynx and penetration-aspiration are associated with pharyngeal weakness. However, they provide little predictive information and therefore have limited value in management decisions: compensatory strategies, decisions regarding enteral feeding, objective monitoring over time or rehabilitation programmes. There are a number of measures of pharyngeal constriction/ strength available. These may provide insight into risk of airway violation and improve surgical decision-making.

Manometry

High-resolution manometry is an established, validated assessment for measuring intraluminal pressures throughout the gastrointestinal tract including the pharynx and pharyngoesophageal segment 8. Key measures from the pharyngeal manometry study include: pharyngeal occlusion pressures, intrabolus pressure gradient and upper esophageal sphincter (UES) pressures. Where there is a high-pressure gradient across the UES, there is likely to be a better surgical response to myotomy or dilatation treatments.

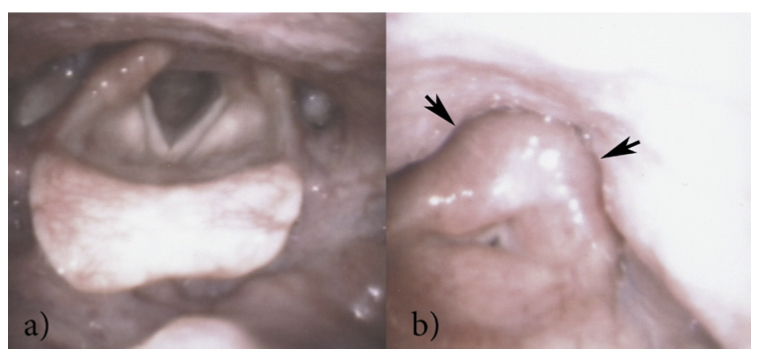

Endoscopic – pharyngeal squeeze

The pharyngeal squeeze is a validated tool for measuring pharyngeal strength during endoscopy 9. The patient is asked to perform a forceful “eee.” The endoscopist observes the pharyngeal wall and documents pharyngeal strength as abnormal if the pharyngeal walls don’t contract medially narrowing the hypopharynx and pyriform fossae (Figure 2). Using simultaneous videofluoroscopy and endoscopy, Fuller & colleagues found significant correlations between pharyngeal squeeze and pharyngeal constriction ratio (PCR).

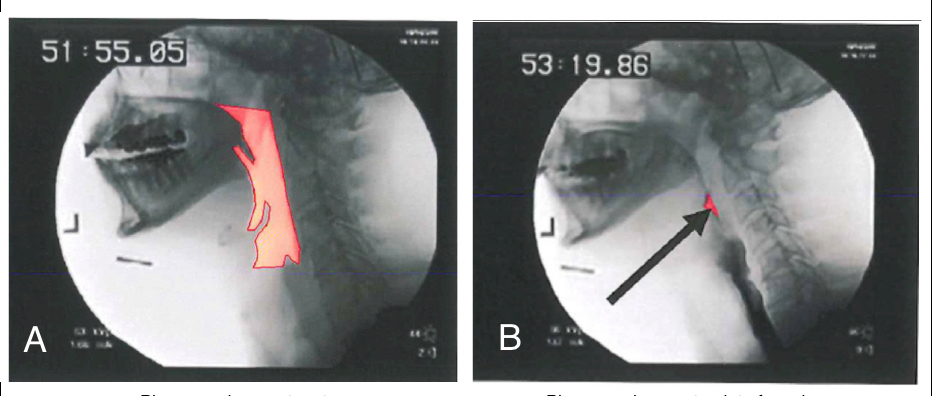

Videofluoroscopic – pharyngeal constriction ratio

Pharyngeal constriction ratio (PCR) is now a well-established tool for measuring and monitoring pharyngeal constriction. It has been validated as a surrogate measure of strength and is correlated with manometric findings 10,11. A metal ring of known diameter is placed on the patient’s chin during videofluoroscopy. The calibrated area of the pharynx can then be measured at rest and then again at maximal constriction and a ratio is calculated (figure 3). PCR should be as close to zero as possible (suggesting complete constriction) and .05 ± .05cm2 is normal for a 20ml bolus 4,12.

A number of other published videofluoroscopic options are available. The Toronto Rehabilitation Institute – Swallowing Rehabilitation Lab have developed a similar pixel-based measure that is anatomically normalized and again involves a ratio of maximum constriction / pharyngeal area at rest 13.

MBSImP

The standardised, validated protocol of the MBSImP™© includes observations of both pharyngeal stripping wave in lateral view and pharyngeal contraction in anterior-posterior view 14.

Why is it important?

Increased pharyngeal constriction (worsened PCR) is highly predictive of aspiration with patients three times more likely to aspirate with a PCR over 0.25cm2 15. In a study of elderly patients with complaints of dysphagia, pharyngeal constriction ratio predicted 75% of all aspiration events 16. Worse pharyngeal constriction scores have also been shown to predict residue scores 13. Pharyngeal constriction, therefore, warrants early identification and treatment. In myotonic muscular dystrophy, Leonard and colleagues found significantly heightened PCR including two patients where the pharynx actually increased in area mid-swallow compared with while holding the bolus in the oral cavity. Abnormal PCR was strongly predictive of residue and aspiration 6. The authors suggest PCR can be used to judge need and timing of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement in this population group 6.

Grossly elevated PCR suggests that pharyngeal weakness is substantial and in the presence of an obstructive pharyngoesophageal outlet, it may bode worse surgical outcomes. In other words, surgical intervention at the UES (myotomy, dilation or botulinum injection) may reduce the outlet obstruction but the effect on swallowing is muted by the weak pharynx which still cannot propel bolus through the UES. Residue often remains significant in this setting.

Recommendations

All clinicians should be reporting measurable pharyngeal constriction values in their patients. It is important to record pharyngeal constriction especially in patients where monitoring over time is critical i.e. neurological disease and head and neck cancer. This will support decisions regarding treatment options over time. A trend of increasing (worsening) PCR may indicate the need for intervention prior to irreversible dysfunction occurring.

Links of Interest

The Swallowing Research Laboratory at The University of Auckland strives to improve the lives of people with swallowing difficulties through improved assessment, treatment and medical education. The laboratory hopes to reduce the risks of pneumonia and death associated with swallowing difficulties as well as improve the quality of life of suffers.

About the Authors

Anna Miles PhD is a full-time faculty member at The University of Auckland. Dr Miles is a researcher, lecturer and clinician in the area of swallowing and swallowing disorders. She is the New Zealand Speech-language Therapists’ Association Clinical Expert in Adult Dysphagia. a.miles@auckland.ac.nz

Dr. Jacqui Allen is a Consultant Laryngologist who specialises in swallowing, airway and voice. Dr Allen is a clinician and researcher, Section Editor of Current Opinion in Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, previous board member of DRS and current member of ABEA, NZSOHNS and RACS. Her grant-funded research has been published internationally and includes collaborations with Engineers, Veterinarians, and Microbiologists. jeallen@voiceandswallow.co.nz

References

- Kendall KA, Ellerston J, Heller A, Houtz DR, Zhang C, Presson AP. Objective measures of swallowing function applied to the dysphagia population: A one year experience. Dysphagia. 2016.

- Ellerston JK, Heller AC, Houtz DR, Kendall KA. Quantitative measures of swallowing deficits in patients with parkinson’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(5):385-392.

- Lan Y, Xu G, Dou Z, Lin T, Yu F, Jiang L. The correlation between manometric and videofluoroscopic measurements of the swallowing function in brainstem stroke patients with dysphagia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(1):24-30.

- Leonard R, Belafsky P. Dysphagia following cervical spine surgery with anterior instrumentation: Evidence from fluoroscopic swallow studies. Spine. 2011;36(25):2217-2223.

- Hutcheson K, Lewin J, Barringer D, et al. Late dysphagia after radiotherapy-based treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5793-9.

- Leonard RJ, Kendall KA, Johnson R, McKenzie S. Swallowing in myotonic muscular dystrophy: A videofluoroscopic study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(7):979-985.

- Allen J, White CJ, Leonard R, Belafsky PC. Effect of cricopharyngeus muscle surgery on the pharynx. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1498-1503.

- Knigge MA, Thibeault S, McCulloch TM. Implementation of high-resolution manometry in the clinical practice of speech language pathology. Dysphagia. 2014;29(1):2-16. Accessed 20140326.

- Fuller S, Leonard R, Aminpour S, Belafsky P. Validation of the pharyngeal squeeze maneuver. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2009;140(3):391-394.

- Lan Y, Xu G, Dou Z, Lin T, Yu F, Jiang L. The correlation between manometric and videofluoroscopic measurements of the swallowing function in brainstem stroke patients with dysphagia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(1):24-30.

- Leonard R, Belafsky P, Rees C. Relationship between fluoroscopic and manometric measues of pharyngeal constriction: The pharyngeal constriction ratio. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2006;115(2):897-901.

- Leonard RJ, Kendall KA, McKenzie S, Goncalves MI, Walker A. Structural displacements in normal swallowing: A videofluoroscopic study. Dysphagia. 2000;15(3):146-152.

- Stokely SL, Peladeau-Pigeon M, Leigh C, Molfenter SM, Steele CM. The relationship between pharyngeal constriction and post-swallow residue. Dysphagia. 2015;30(3):349-356.

- Martin-Harris B, Brodsky M, Michel Y, et al. MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment- MBSImp: Establishing a standard. Dysphagia. 2008;23:392-405.

- Yip H, Leonard R, Belafsky PC. Can a fluoroscopic estimation of pharyngeal constriction predict aspiration?. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(2):215-217.

- Kendall KA, Leonard RJ. Pharyngeal constriction in elderly dysphagic patients compared with young and elderly nondysphagic controls. Dysphagia. 2001;16(4):272-278.