The aim

The aim of this article is to give voice to a small group of children at the lower level of functioning and with many health problems. They are children with profound multiple learning disabilities (PMLD). They will be technology dependent and have lifelong needs. They are very fragile and very often they will not reach the symbolic level in communication. Their language is basically a body language that demands a high degree of sensitivity and responsivity from the people around the children.

Most of all they are children with a big desire to communicate. We will call them Une from now on.

Many of these children struggle with Dysphagia. Many get nutrition through a PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) and after some accommodations the PEG is replaced with a low- profile gastrostomy-button (G-button). Many parents and professionals will name it simply “button”.

The story of Une is a story many parents and caregivers can recognize. Below, Une’s mother and Une’s relief personnel tell of her story.

Une’s mother tells how it was when Une was a baby

Une baby

“The new button pads are so good”, says Une’s mother. Here is her story. “Une likes them a lot, but not because of their fun designs. She is not able to see those – it is because they feel nice and soft towards the skin. Previously, it was a tube in her nose that gave her nutrition. I thought: What would we have done without the nasal tube? However, I also saw what a problem it was for her. She vomited a lot and the food often came up. I was trained to re-insert it. I would rather have avoided this – but in a way it was expected, and so I consoled myself by saying to myself: We avoid several visits to the hospital during certain periods.

“Try to reflect about the environment both physically and emotionally. Both have an extreme importance in the feeding-eating function of the child.”

Une had an operation to insert the button when she was only 10 months old. Up to that point, breastfeeding had been on-off. On some days she managed to feed a little. I hoped it would get better so I could sit and enjoy the time with my baby feeding from my breast. The fact that I could not even give her that, made me feel really, really low. I wanted someone to tell me that everything would be okay soon, that she would feed by herself again. I asked a doctor, several doctors. Feeding was more important than asking when Une would begin to talk. Indeed, occasionally I also thought about that. But feeding was life itself for Une”.

Parents tell often that doctors and nursing staff seem to avoid answering the question about PEG. “A nurse mentioned something about “a button on the tummy”. I had never heard of it. They said it was also called PEG. I had to Google to find out”. Did it mean that she would never be able to eat? It was so definitive. It seemed to be so permanent. In truth, I didn’t want to go ahead. But we decided to go for the button. Someone convinced me to go along with it”.

The button was inserted and frequently used for food and medicines. Une got more energy and got stronger. After a while, parents love the button because it gives them the opportunity to see the child having time to look like the child, to feel her, to get to know her and touch her, talk with her. Nutrition is guaranteed.

They are certain that Une did not die of hunger… and not least, they had the energy to talk with her.

“Une’s story is a happy -end story. Nutrition is guaranteed. Parent and caregivers underline the importance to understand their signals. Mealtime is the smell of pizza on Saturday. “

Une has started to feel that she is hungry. The button became not just a health issue. It is important that parents and caregivers regarded the button as a part of eating and that they never forgot that Une has a mouth, that Une can turn away to say “wait a little”, begin to get full, just let me feel the smell. Parents have “time” and energy to see her push away the bottle and to be able to respond to her. The mother says: “Mealtimes with Une mean something else now. It is so good to see that she prefers nutrition drinks with chocolate flavour instead of strawberry flavour. Mashed up fish ball, a finely minced meatball or just the sauce on some days. Yes, I call that eating, a mealtime, and not least we call it that when we sit together around the table”.

Une’s relief personnel tell how it was as Une grow up

Une has grown

“Une, a girl with multiple disabilities, is first and foremost a child – a little girl with a beautiful smile”, say Une’s relief personnel.

“She strives in allowing us to take part in her joy, but she shows that she wants contact by turning her little body and trying to reach the spoon. She has several disabilities, which means that she has to live with a body that has to be arranged, straightened up, calmed down and fed regularly. She loves the smell of pizza on Saturdays and looks forward to tasting the sauce – but most of her nutrition runs slowly but surely through a probe in her stomach. Despite nausea and vomiting, Une seems happy to sit at the dinner table. We have realised that very rarely does vomiting occur without prior notice.

The impressions that Une receives from the outside and inside melt together in an experience that for Une and her carers, often appears to be mystical and incomprehensible, and this makes both Une and us unsure. However, we practice in reading Une, and listening to what her parents tell us. We learn from each other” conclude Une’s relief personnel.

Une’s story is a happy -end story. Nutrition is guaranteed. Parent and caregivers underline the importance to understand their signals. Mealtime is the smell of pizza on Saturday.

For children like Une mealtime represents a challenge. In addition to the oral motor problem, learning to eat is for Une furthermore complicated because she can neither label the bodily impression of food nor take advantage of role model around the table. Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI) can contribute to give her an unclear picture of food. Hearing problems can amplify and make for instance the sound of a metallic spoon unpleasant. These factors can contribute to give Une a further anxiety for what’s going on around the table.

But she has to eat. The caregivers say often: “Yes but she had to eat”. There are many children who have to eat. The practice of conversation that is the main part of a mealtime is no issue. They are not only disabled but not audible too. In other words, they do not have a voice.

The voice of the preemies

Preemies I met in my practice have taught me what Une cannot tell by herself.

I have learned a lot from preemies age 8 to 11 years met in my habilitation practice. The following quotations have put track in my memory. They tell us something about the fear to swallow. Further on the children construct some narratives. Through these narratives they try to make sense of the troubled situation they experience. How they imagine the process of chewing and swallowing.

”Teeth rest while eating mushed food………..”

”The throat stops here…………..”

”The food waits for the elevator, before going downstairs to the hotel rooms”

I chew with my tongue.

The teeth are on holiday. But now they are back from holiday. But could they please take days off on Saturday ….and Monday…..?

I don’t like cold food. It’s so cold. It hurts my tongue.

Don’t give me more, mom. I’m feeling sick (nauseous)

”Your food looks delicious….”(”Do you want to taste?”) ”No No.”

I cannot forget Dennis, a boy in a kindergarten. He told the caregiver in the kindergarten that he was satisfied. The caregiver insisted that he should eat some more. Dennis vomited and after that he said to the caregiver: “Is not that what I told you, Petter? And now you have to wash up”.

Another child said to his mother: “It is enough mum!” The mother was so shameful because of the prescription she had to follow.

These are powerful stories. The children have a voice and they use it.

Implication

We can presume that also Une thinks something like that. But her voice is not the usual one. Because the voice is not the usual one, it is not audible.

We decide for her.

We do not ask about what she likes, which is her best mealtime during the day, which temperature. What does she think when she eats porridge day in day out? We have to listen to small signals and make them part of the mealtime conversation.

We presume that chocolate is for instance something everybody likes, especially children.

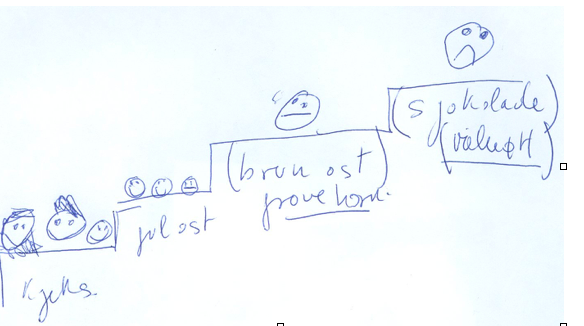

The drawing below shows what a premature girl thinks about different sorts of food. For her, chocolate is really bad tasting on the top of the stair. Cookies are better but a cookie is not like the other one and she was very exactly describing the difference between three different cookies (norw.kjeks). The same for different sorts of cheese (norw.gul ost).

As said at the beginning of this article, Une has three main problems beside the oral motor difficulties. Une has a very bodily impression of what she eats-tastes-smells -drinks without the possibility to label what she eats-tastes- smells- drinks. She cannot really fully take advantage of the other around the table and use the advantage of role models.

Therefore, Une is a very vulnerable child and extremely dependent during mealtime from a sensitive and responsive meal-time partner to mirror the bodily expression and give it back as response inside a communication frame. To label with a soft voice the food. To connect her to the others. To ensure her that the scary sounds in the environment are not dangerous.

Conclusions

When the caregivers are sensitive, aware, they can feel secure about the signals from the child.

For instance, the caregiver of a boy told: “I feel something is coming up (nausea) and I begin to sing and it can function”. Another caregiver told me about colour change in the face “ and I stop feeding”.

They tell us that they understand – try to understand – the tiny signals from the child and respond in such way that feeding can be a good mealtime experience.

Une cannot explain such feeling of difficult swallowing with words. It is up to us to understand the lot of messages she expresses with body language. Don’t make assumption without having tried to ask the child first.

Try to reflect about the environment both physically and emotionally. Both have an extreme importance in the feeding-eating function of the child.

I end this article with the story of Lukas’ breakfast and what his special teacher, Gro, highlights.

“Breakfast is also quieter for me, and my attention to Lukas’ signals is more focused. Communication and interaction between me and Lukas has more of a starting point in Lukas’ signals.

I follow Lukas’ gaze and comment on what he sees. I feel that I can more easily be aware of and act on his sounds and small movements, and I respond to these with my sounds, movement and words. We have several small and good “conversations” during a breakfast.

The calm atmosphere also means that the “sensuous” aspect of the meal is more clearly evident. The flickering of the candles, the smell and steam coming from my teacup, the taste of liver pâté – more is noticed, more is described, commented on and spoken about.

Breakfast has become a fine time with calm, sensory experiences, communication and interaction for me and Lukas”.

Editorial Note: I am so thankful for the international contributors to Dysphagia Cafe. This is Ena’s Third article that she has authored. Please see her previous article “Eating together is an act of love.”