What is trismus?

Xerostomia, oral mucositis, surgical reconstruction, impaired wound healing, dysgeusia, irradiated tissue and dysphagia. Most medical SLPs who treat head and neck cancer patients are well aware of these unfortunate side effects of cancer treatment. A lesser known evil, but almost just as common, is trismus. Trismus is characterized by a mouth opening of 35 mm or less and patients can be diagnosed as mild, moderate, severe, or profound trismus according to Dijkstra’s trismus severity criteria (Dijkstra et al., 2006).

Those at risk for developing trismus are patients who have undergone:

- Radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

- Surgical reconstruction of the oral cavity or oropharynx regions

- Have tumors as the sites of the muscles of mastication and/or TMJ

Trismus can negatively impact the patient’s mastication abilities, speech intelligibility, oral care, dental care, airway patency, and quality of life.

Which patients acquire trismus and why?

Recent research indicates that radiotherapy to the ipsilateral medial pterygoid and ipsilateral masseter muscles in approximately 60 Gy dosages is the biggest predictor of trismus acquirement (Kraaijenga et al., 2019). Since these critical muscles are often included within the targets of radiotherapy, it is not surprising that as much as 70% of patients irradiated for oropharyngeal cancer are at higher risk of acquiring trismus (Pauli et al., 2016). Radiation fibrosis syndrome (RFS) is to blame for much of trismus. When RFS infiltrates the tissues of the oropharynx or oral cavity, it causes the tissue to become hardened over time, which consequently results in a reduced range of motion. Without therapeutic intervention, the patient with trismus will continue to lose range of motion and function. Although it is difficult to know exactly when a patient will start to experience the effects of trismus, research tells us that head and neck cancer patients will likely start experiencing a decline in mouth opening at 3-6 months status post cancer treatment (Pauli et al., 2013), but the timeline can vary based on a variety of patient factors.

When should trismus intervention be initiated?

Unfortunately, trismus is not a condition that can be proactively treated with exercise. In a 2011 nonselective, longitudinal, prospective cohort study evaluating the effect of the experimental early preventive rehabilitation of 190 HNC patients, researchers found no positive effect of early preventive rehabilitation (Ahlberg et al., 2011). In Dijkstra’s 2016 systematic review of preventative trismus intervention studies, five of the eight studies found that exercises during chemoradiotherapy did not prevent jaw opening reduction. Again, these findings are not surprising. As Pauli’s 2013 study shows us, RFS does not start to rear its ugly head at the start of radiotherapy. RFS-induced trismus takes time to develop.

What are evidence-based practices in trismus intervention?

Sadly, RFS-induced trismus is a life-long medical condition that needs to be managed with daily exercises. According to leading trismus researcher, Dijkstra, “Exercise therapy is the mainstay of treatment and exercise should start as soon as possible after cancer treatment” (Rapidis and Dijkstra et al., 2015). However, while some medical SLPs may have heard about and see their head and neck cancer patients struggle with trismus, many SLPs are not trained to treat it safely and effectively. As a result, they may use universal device instructions, such as the 5-5-30 or 7-7-7 with jaw mobility devices like the TheraBite, OraStretch, or perhaps stacked tongue depressors. These universal exercise regimens with arbitrary exercise prescriptions are not tailored to the patient’s individual needs and frequently lead to a plateau in progress, patient frustration, and poor exercise adherence. Imagine going to the gym, paying for a trainer, and instead of obtaining an individualized exercise plan, you receive a list of exercises you could have found online. This scenario is akin to giving a patient with trismus instructions from the device, not using exercise principles and therapeutic techniques based on the patient’s pain level, challenge level, and goals.

Trismus intervention requires both passive jaw stretching to increase mouth opening range of motion and active jaw stretching to improve rotary chewing range of motion and disuse atrophy. Passive jaw stretching includes any jaw mobility devices, such as TheraBite, OraStretch, JawClamp, and ARK-J Program Stretching Device, but the patient can do manual jaw depressions with his or her hand or a clean TheraBand if he or she cannot obtain a device.

Stacked tongue depressors have been used to treat trismus by dentists, oral maxillofacial surgeons, and ENTs for decades, but:

- They are not ideal since they lack calibration.

- They are not gentle on the TMJ due to lack of give.

- They can damage brittle teeth that are more vulnerable after radiotherapy.

- Should only be used when a jaw mobility device cannot be used due to patient’s jaw opening being less than 10 mm (minimum for most devices).

Active jaw stretching includes gum, sponge toothettes, chewy tubes, and stretch bands that come with the TheraBite and OraStretch that can be used to remediate the vertical chewing pattern and disuse atrophy that can form with trismus. Complementary approaches, such as myofascial and manual release, are beneficial to improving the fibrosis so that stretching can be maximized. Lymphedema therapy should be utilized if jaw range of motion is restricted due to lymphedema.

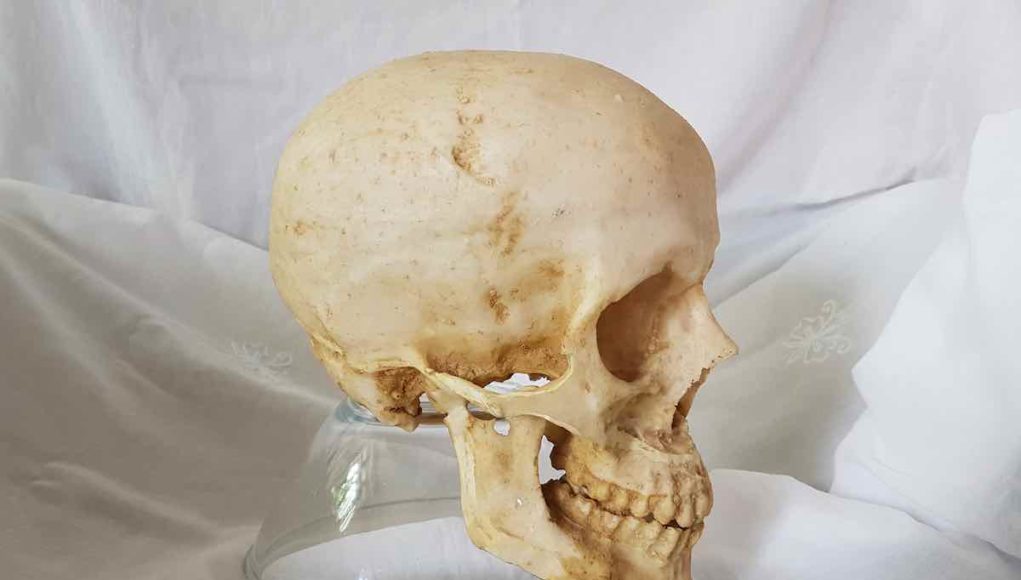

What is ORN and which patients are considered high-risk?

Clinicians who treat patients with trismus should also be educated on a dangerous medical condition called osteoradionecrosis (ORN), which is bone death or necrosis from radiotherapy. ORN can develop at anytime after radiotherapy and often appears as a small, asymptomatic region of exposed bone that can easily be misidentified as a receding gumline or missed in the midst of surgical reconstruction scars. Over time, the patient will develop severe, constant pain. Treatment for ORN can be a difficult road, so the key is to catch ORN as early as possible.

According to Owosho et al.’s 2017 study, the risk factors for ORN include:

- Poor dental health prior to radiotherapy

- Pre-radiation exodontia in the radiation field

- Continued use of alcohol and/or tobacco during radiotherapy

- High dosages or multiple courses of radiotherapy

Clinicians should frequently perform oral exams on trismus patients and train them to do self-exams to ensure early detection of ORN. Patient reports of pain should always be taken seriously and investigated further. If ORN is detected during treatment, exercises should be halted, and the MD should be contacted immediately. Patients with active ORN should not be participating in trismus therapy due to the risk of fracture, infection, and increased pain. As with any start of care, the clinician should obtain a physician’s order to provide trismus therapy.

Trismus therapy should be safe, progressive, and tailored to the patient’s needs. SLPs who treat trismus should be:

- Up to date on the latest trismus research

- Understand the pitfalls of trismus therapy

- Know how to identify ORN

- Educated on evidence-based therapeutic tools and techniques

- Use exercise science principles, not arbitrary or universal device instructions, to prescribe individualized exercise programs to increase patient exercise adherence, minimize chances of plateau, and ensure success in reaching patient’s therapy goals.

If an SLP has not been trained to evaluate and treat trismus, he or she should seek mentorship from an experienced, trained clinician or refer the patient to a trained SLP.

Clinical resources, trismus research, trismus intervention training, and a directory of trained trismus therapists can be found at www.ARKJProgram.com.

References

Ahlberg, A., Engstrom, T., Nikolaidis, P., Gunnarsson, K., et al. (2011). Early self-care rehabilitation of head and neck cancer patients. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 131(5).

Dijkstra, P. U., Huisman, P. M., & Roodenburg, J. L. N. (2006). Criteria for trismus in head and neck oncology. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 35(4), 337–342. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1 016/j.ijom.2005.08.001

Kraaijenga, S. A., Hamming‐Vrieze, O., Verheijen, S., Lamers, E., Molen, L., Hilgers, F. J., … Heemsbergen, W. D. (2019). Radiation dose to the masseter and medial pterygoid muscle in relation to trismus after chemoradiotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer. Head & Neck, 41(5), 1387–1394. doi: 10.1002/hed.25573

Owosho, A. A., Tsai, C. J., Lee, R. S., Freymiller, H., Kadempour, A., Varthis, S., … Estilo, C. L. (2017). The prevalence and risk factors associated with osteoradionecrosis of the jaw in oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients treated with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center experience. Oral Oncology, 64, 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.11.015

Pauli, N., Fagerberg-Mohlin, B., Andréll, P., & Finizia, C. (2013). Exercise intervention for the treatment of trismus in head and neck cancer. Acta Oncologica, 53(4), 502–509.doi:10.3109/ 0284186x.2013.837583

Pauli, N., Olsson, C., Pettersson, N., Johansson, M., Haugen, H., Wilderäng, U., Steineck, G., et al. (2016). Risk structures for radiation-induced trismus in head and neck cancer. Acta Oncol, 55(6), 788–792. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2016.1143564

Rapidis, A. D., Dijkstra, P. U., Roodenburg, J. L. N., Rodrigo, J. P., Rinaldo, A., Strojan, P., Takes, R. P., et al. (2015). Trismus in patients with head and neck cancer: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Clin Otolaryngol, 40(6), 516–526. doi: 10.1111/coa.12488.