This is a sponsored post for the Mobili-T®. For more information, please visit: https://www.trueanglemedical.com

When I first started working as a clinician, I used to send patients home with a list of dysphagia exercises to complete. Sometimes I’d see these patients a week later, sometimes not. Our conversations would usually go something like this:

Me: “How did the exercises go?”

Patient: “Good.”

Me: “Were you able to do them?”

Patient: “Yes.”

Like so many other clinicians, conversations like this made me feel like I was working in the dark; I had no idea what my patients were really doing at home. When I tried using tracking sheets, I rarely ever got anything back.

That’s when I realized that we needed something different. I looked at the smartphone on my desk and knew I had multiple apps that were doing the tracking for me. I could instantly see how many steps I took that day and how that compared to last week’s average. I could see my running speed and how many workouts I logged. And all this information was being tracked without me having to record a single thing by hand.

Smart technology is all around us, so why are our patients still using pen and paper?

Mobili-T – a mobile system for swallowing exercise

Fast forward a few years: I’m now part of a team at True Angle who has created Mobili-T®. Mobili-T is a mobile system that uses sEMG (surface electromyography) sensors to not only provide patients with biofeedback during swallowing exercise, but also track their exercise and progress, and make that available to you, their clinician.

The Mobili-T is made up of:

- A small sensor device

- A smartphone app

The small device sticks under the chin using double sided adhesive. The Mobili-T uses sEMG sensors to detect muscle contractions during swallowing exercise. It sends information about muscle contraction to the app via Bluetooth. The app then displays real-time visual feedback of muscle activity. When muscles contract, the line goes up. When the muscles relax, the biofeedback line flattens.

sEMG biofeedback has been shown to be a great adjuvant to swallowing therapy1. Mobili-T is easy to use and convenient to pop in your pocket. For us as clinicians and researchers, it also tracks adherence. In other words, it tracks how many reps your patient completed, as they exercise.

Over the last few years, the topic of adherence has come into the spotlight in our field, from conference presentations to recent publications2-5. How much does the typical clinician think about adherence though?

Adherence – what is it?

During my postdoctoral fellowship, my supervisor (an epidemiologist) quickly taught me the distinction between adherence and compliance, as he noted that I used these terms synonymously. He told me compliance is a passive rule-following behavior, whereas adherence is a proactive one and suggests the patient is playing a more positive and active role in their own care. Treatment adherence is “the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with the agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider” (World Health Organization). While this is a nice definition, it leaves the operational description of adherence open. Hence the measurement of adherence has been noted to vary from a binary choice (adherent vs. non-adherent) to diaries of reps completed (patient reports they completed 7 out of 10 reps on a given date)2.

Reported measures of adherence can also vary based on whom you ask. When asked how much they thought their patients were sticking to assigned exercises, some clinicians answered an astounding 75 to 100%6. Patients on the other hand reported adhering to their swallowing exercises during radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy 58% of the time7. However, when using demonstrated competency with the prescribed exercise, only 13% were considered fully adherent8.

Adherence numbers can also vary depending on whether adherence is captured weekly over the course of a treatment program (e.g., week 1 – 100%, week 2 – 80%, week 3 – 60%, week 4 – 50%) or simply reported as a single number over the course of the program (72% over 4 weeks). I point this out because granularity matters with respect to adherence. The goal shouldn’t be to average out any trends, but rather to gain visibility to them.

Why is adherence important?

Without knowing adherence we’re essentially working in the dark. Imagine a situation where we recommend to a patient (based on their pathophysiology, or disordered swallow process) that they complete 10 effortful swallows a day, every day for 6 weeks. At the end of their treatment program, we complete an instrumental assessment, notice no difference in function and conclude that the effortful swallow for 6 weeks must not have worked for this patient. Ten effortful swallows a day was the recommended dose. But what was the dose taken? What if this patient completed 2, or zero exercises a day? Understanding adherence helps us make informed decisions about the effectiveness of our exercise programs2,3,5. It lets us know what to do next.

What does the research say about adherence?

In her systematic review of the literature, Krekeler found only 3 studies (out of 12 included) that used a count of reps to capture adherence with an average adherence of 51.3%1.

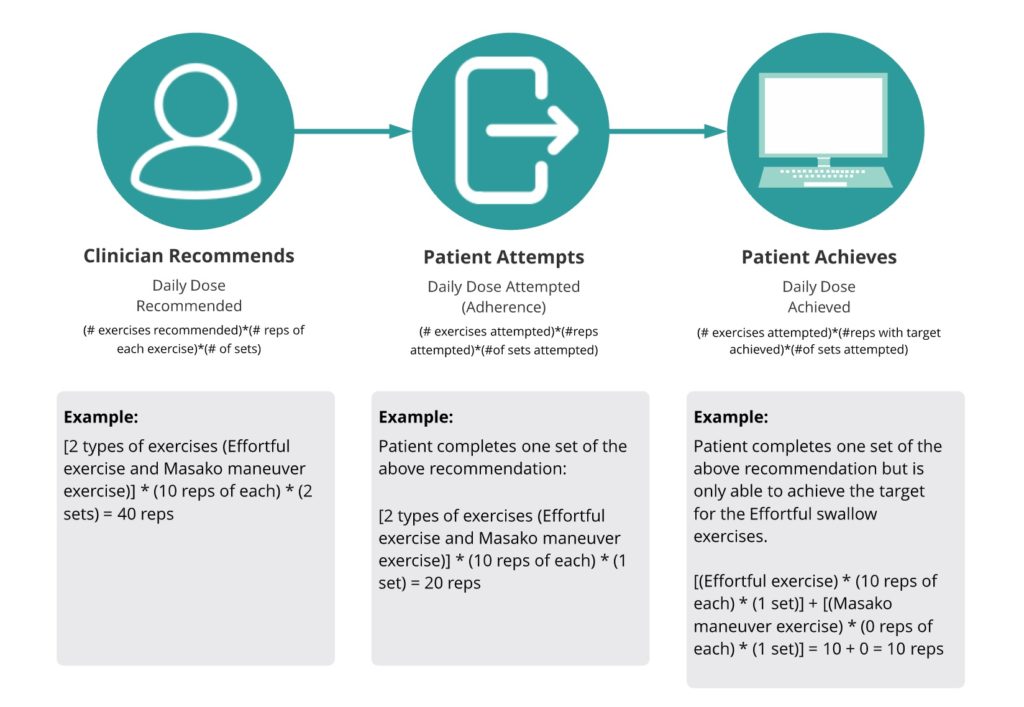

We recommend the following operational definitions for adherence: (total number of reps completed / total number of reps recommended) *100. Another way to think about adherence is to say it is the daily dose of attempted vs. recommended exercises.

Consider the following recommended definitions:

This works great for researchers, but I don’t have the time or expensive equipment.

This has been true up until recently. Capturing adherence has primarily been achieved through self-report, either using pen and paper or apps. However, the technology is there for us to move beyond pen and paper and use more sophisticated measures.

Think about some of the ubiquitous step-tracking apps out there such as the Health app (Apple). It’s remarkably easier when these technologies measure how many steps we’ve taken so that we can focus on getting the exercise and worry less about counting, writing numbers down, remembering where we wrote it last, and beyond that – doing something meaningful with that information.

Imagine if you could do that for swallowing exercises in home programs. How would tracking adherence in an objective way change the conversations you’re having with your patients?

Adherence with Mobili-T®

A target line is calculated each time the patient uses the Mobili-T. This target is a percentage of the patient’s current ability (as well as current device placement and their workout setting).

Using the Mobili-T lets patients track the proportion of exercises they completed from their recommended program (daily dose attempted, or adherence) as well as how many exercises they completed where the target was achieved (daily dose achieved).

Mobili-T® for clinicians

When a patient uses the Mobili-T at home (or in their hospital room), their daily adherence can be monitored, (i.e., dose attempted), as well as their daily dose achieved.

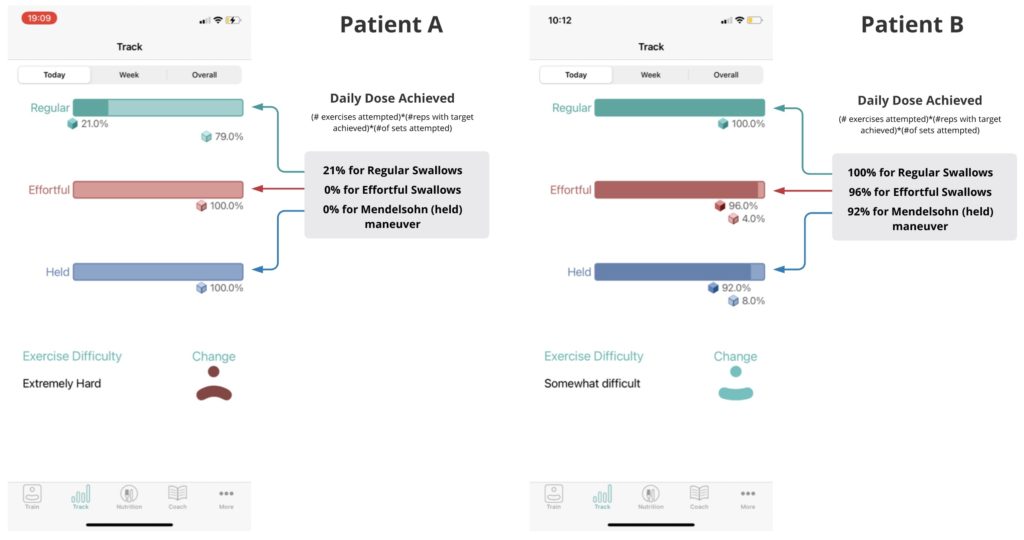

Mobili-T shows this in real time, as the exercises are completed. The display uses different colours to denote different exercise types: cyan for regular swallows, red for effortful swallows, blue for Mendelsohn maneuver swallows. It also uses colour intensity to denote targets achieved versus not achieved: solid colour for reps attempted and target achieved, faint colour for reps attempted and target not achieved.

In the example below, you can see that both patient A and B completed all the reps they were asked to do for that day, but patient B achieved the target for most reps, while patient A did not.

Example:

Both patients A & B received the same exercise program:

- Daily dose recommended = (3 exercise types) * (3 reps of each) * (8 sets) = 72 reps

Also, both patients A & B completed all reps, or in other words have 100% adherence.

- Daily dose attempted (adherence) = 100% for all exercise types

However, the daily dose achieved was different.

We are on the precipice of an exciting opportunity in our field.

As I write this, I am excited for the opportunities that a technology like Mobili-T can bring to our field. For patients, it’s biofeedback in the palm of their hand. No longer is an easy, non-invasive technology locked behind doors of a hospital that can afford to purchase expensive equipment. For clinicians, it means rich conversations with patients around facilitators and barriers to practice outside of your clinical sessions – you know, where the bulk of the work on dysphagia happens. And for researchers like me, it means being one step closer to understanding exercise dose response.

For more information about the Mobili-T® device, visit: https://www.trueanglemedical.com

References

- Albuquerque LCA, Pernambuco L, da Silva CM, Chateaubriand MM, da Silva HJ. Effects of electromyographic biofeedback as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of swallowing disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(4):927-38.

- Krekeler BN, Broadfoot CK, Johnson S, Connor NP, Rogus-Pulia N. Patient Adherence to Dysphagia Recommendations: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia. 2017.

- Krekeler BN, Rowe LM, Connor NP. Dose in Exercise-Based Dysphagia Therapies: A Scoping Review. Dysphagia. 2021;36(1):1-32.

- Krekeler BN, Vitale K, Yee J, Powell R, Rogus-Pulia N. Adherence to Dysphagia Treatment Recommendations: A Conceptual Model. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2020;63(6):1641-57.

- Krekeler BN, Yee J, Daggett S, Leverson G, Rogus-Pulia N. Lingual Exercise in Older Veterans With Dysphagia: A Pilot Investigation of Patient Adherence. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2021;64(5):1526-38.

- Krisciunas GP, Sokoloff W, Stepas K, Langmore SE. Survey of usual practice: dysphagia therapy in head and neck cancer patients. Dysphagia. 2012;27(4):538-49.

- Hutcheson KA, Bhayani MK, Beadle BM, Gold KA, Shinn EH, Lai SY, et al. Eat and exercise during radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for pharyngeal cancers: use it or lose it. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(11):1127-34.

- Shinn EH, Basen-Engquist K, Baum G, Steen S, Bauman RF, Morrison W, et al. Adherence to preventive exercises and self-reported swallowing outcomes in post-radiation head and neck cancer patients. Head & neck. 2013;35(12):1707-12.